Studying History with the Help of Free Association Drawing

For over ten years at Step Up, I’ve been teaching history to young people diagnosed with severe disabilities who live in Moscow’s psychoneurological institutions. Most of our students stand no chance of finishing school. That’s why I think it is very important to boost their standing in their own eyes. We put on exhibitions and presentations, we print out their work for internal use. It would be absolutely wonderful if their work could draw the interest of other people from the “big world,” not just ours.

Our students come to Step Up as adults. These young people are orphans. They live in psychoneurological institutions, and at some point they were deemed “unteachable.” That’s why many of them didn’t know how to read, write or count when they came to us. Bu they made a conscious decision to come here, with a great desire to learn, prepared for years of hard work and with a very clear goal in mind: to get a regular education and learn a trade. At the same time, many have another goal: to leave their psychoneurological institutions having proved themselves capable of living independently to the people who make these decisions.

For our students, studying Russian history has paved the way to discovery, to adapting socially, and to resolving psychological problems through analysing historical processes, fates and events.

When the subject matter is exciting and gripping, it is easier to learn to read, write, count, think, to speak clearly and cogently, as well as to find your own topic, your calling.

History can be studied in a number of ways. There are diverse cognitive tools that should be used if the goal is to process and absorb historical facts, rather than just listening or picking up information from a text. One can also use gestures, the sense of smell, taste and touch, theatre, music, poetry, design, sculpture and visual arts…

Drawing is a different level of communication and understanding, another language. Not everything can be said with words.

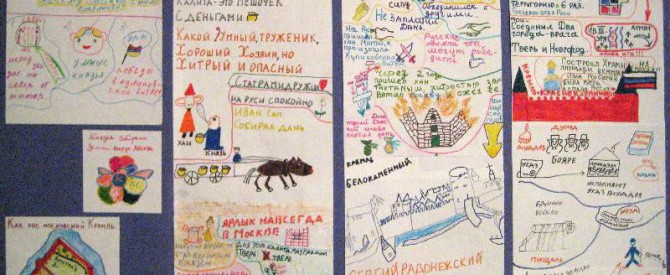

If you pick up paints or pencils, you can experience and transform what you’ve discovered into your own symbols. Shapes and colours start working for you. Your hands create and memorize, helping you make unexpected discoveries while you draw or look at a finished picture. You are not a passive listener, but rather the creator of your own story.

Referring to images in history lessons activates the right half of the brain, thus supplementing the left half, which is responsible for logic. This natural union of the two halves results in a lively “thimage” (thought + image). The more unusual and relevant to its creator it is, the more effectively it alleviates the stress and fear of mastering difficult material through “familiarization,” empathy, association and creativity. The student’s imagination and life experience, as well as study materials, are used to create. As a result, the student learns to process information using a new technique: the habit of thinking figuratively.

Trusting the teacher, following him or her down a new path, taking a risk and sketching out information are not easy tasks for our students. They haven’t studied much and have never learned any subject this way. We move gradually: from words shortened to just one symbol, from little icons and pictures (like Egyptian hieroglyphics) to base plates and artistic images.

In essence, this approach is a return to ancient Russian chronicles. The students create a kind of chronicle of their native history: they write down the things they deem important, and, by using their figurative, associative thinking, sketch out the things they find interesting.

As a result, every student has his or her own illustrated history book, which gets thicker with every year. When you have your own book and posters on your walls, you can easily take “historic walks” in different directions: recollecting, comparing and drawing conclusions.

Every time I start down this road with the students, I vacillate: will they accept it, will it work and will they like it? And every time I see that having experienced creative agony, they don’t emerge burdened with new information, but liberated, bright-eyed and surprised by the fact that they thought they couldn’t do it. And yet they did it, and enjoyed it, as others have done. Drawing after being “overloaded” with new information is like exhaling after holding your breath for a long time.

Drawing… there is something childish, something unsubstantial, about such a pastime. This must be the barrier for adults, as well as for those who consider themselves adults. Would many teachers agree to draw something on a blank piece of paper? But it’s not for nothing we are told to act like kids. If you take the plunge, you will not stand still, but keep moving and become real, true grown-ups.

It’s not just that our students benefit from drawing (it helps to develop manual dexterity, and aids psychological rehabilitation), but they also get in the habit of needing to express themselves through creative arts. Gradates of a school that nurtures creative energy are truly ready for self-education, self-identification, and for independent living.

The study of every historical period is achieved through a set plan:

- We read a short text, study the illustrations and try to understand, analyse, discuss and add our own thoughts;

- We think of a way to extract the main ideas and to write this idea down in the shortest way possible;

- We think about the images that would reflect the essence of what we have read;

- Everyone acts on their thoughts (including the teacher) while writhing in a sort of productive creative agony;

- We read and process the next idea;

- During the next lesson, we re-visit the drawings and our notes, and then we move on;

Every topic is wrapped into a group project: we collect everything onto one poster (every student draws a piece of their choosing). Then we reinforce and apply the knowledge through holding contests, putting on presentations for guests, and so on.

All students start drawing in history class. They try different approaches and drawing techniques, eventually settling on their own, unique style that turns them into original artists. All of them! Is that a miracle? How does it happen? What do the students need in order to succeed?

- They need the opportunity to work hard: to take a long time to examine an enthralling subject, to be able to find information, to think it through and to accept it, to learn to apply it, to discuss, to ask questions and to speak their minds.

- They need the ability to realize that when you want to express your thoughts on a piece of paper, the notion “I can’t draw” doesn’t exist. On the contrary: the more of myself I put into it, the less it looks like something someone has already drawn, and the more interesting and valuable the work will be.

- They need the full, unwavering support of an interested and authoritative teacher, who creates a welcoming atmosphere conducive to teamwork and creativity.

- They need a place, a time and the materials to draw freely. When a subject lives inside of you, you can just let your hand move freely, unrestrained – and enjoy it.

- Finally, it’s nice to have the ability to show your work and receive positive feedback from outsiders at exhibitions, presentations, conferences, and in publications.

Our students have very complicated backgrounds. They weren’t sufficiently educated in time. But they possess outstanding human qualities, an unmatched intuition and the ability to think creatively. The result of our collaboration during history lessons is twofold: learning new material and creating works of art.